Spoiler-free

I saw Kyle Edward Ball’s 2022 experimental horror film Skinamarink for the second time last night. In stark contrast to the first time I saw it (alone, in my room, watching a pirated copy that had been causing the film to gain some buzz on Twitter), this time I was watching it in a packed cinema at the Lido with several of my friends and some of Melbourne’s most prodigious Letterboxd weirdos in attendance. I could not tell you what percentage of the audience were seeing the film for the first time, but I can say with relative certainty that it was almost everyone’s first time seeing it in a cinema (the only previous screening in Melbourne had been the night before). The experience was different, to say the least, but I found Skinamarink to be no less groundbreaking, fresh, and exciting than before.

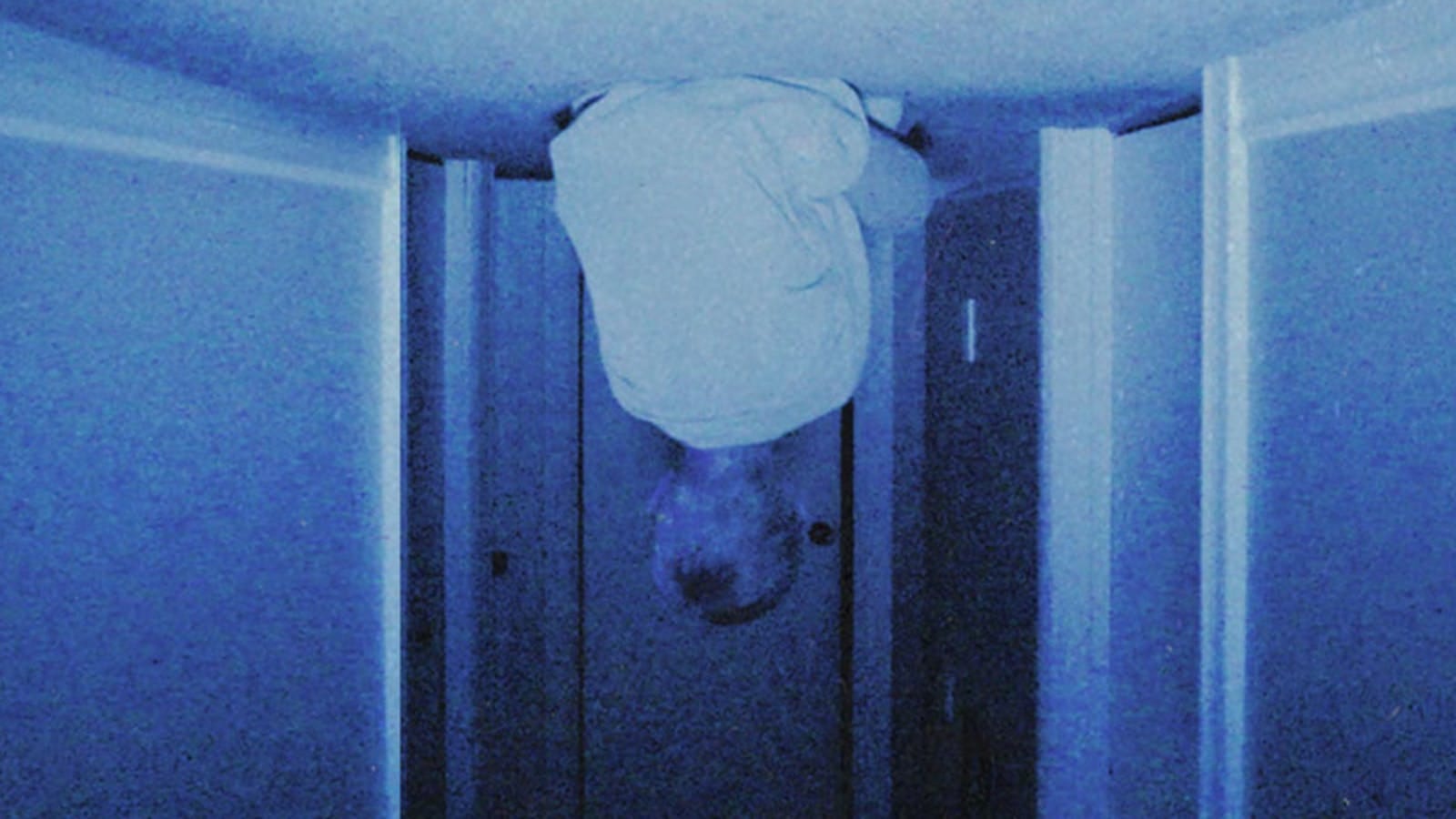

There is very little plot in Skinamarink. The film consists primarily of static shots of the interior of a house, dimly lit and caked in digital grain. Much of the aesthetic stylings can be attributed to the film’s remarkably low budget (just $15,000 USD), but working within those constraints, Ball crafts a stunningly unique visual and aesthetic experience which draws as much from experimental cinema as it does from the annals of horror history. In particular, one can keenly feel the influence of structural filmmakers such as James Benning or Michael Snow, and I would go so far as to say that, on an aesthetic level, Skinamarink has far more in common with that filmmaking movement than any other horror film that I’ve seen. Watching it for the first time I had little experience with structural film, but reading reviews which made references to films such as James Benning’s Maggie’s Farm (2020) or Chantal Akerman’s Hotel Monterey (1973), I felt compelled to explore the few to which comparisons could be made. Watching it for the second time with this added context, it was surprising how neatly it fits into the framework. The extensive use of static camera angles and flickering lights are two key characteristics of structural cinema. Of course, Skinamarink is a horror film and, as such, Ball projects pure nightmare fuel onto this framework. The little light there is comes from small sources such as lamps or night lights and, most prominently, the blue glow of the tv. Most of the film is awash in blue light or pitch black and much of what is shown on screen obscured or unrecognisable. The addition of startling amounts of film grain provides a textural fuzz to everything shown which abstracts the images away from any sort of familiarity, creating a discomforting sense of spatial unreality.

On the narrative side, I came out of my first viewing thinking that it had almost none. On the second however, the story became a little clearer. Siblings Kevin and Kaylee wake up one night to find that the windows and doors in their house have disappeared and begin to be terrorised by a mysterious (and terrifying) entity which takes on many forms, including that of their parents. It reads like a classic horror concept, evoking a childhood fear of the dark (the title also references the popular children’s song) as well as a typical horror subversion: turning the assumed safety of domestic space into something nightmarish. The stroke of brilliance in the film is where the aesthetic stylings meet this typical horror narrative, presenting it in such a way that makes it feel unlike any other horror film. Ball begins to instill the viewer with a familiarity of the children’s surroundings and the spaces in which the film takes place. Several locations are revisited and become recognisable but are frequently only shown in fragments and segments, never quite allowing us to fully grasp the interior of the house. You begin to crave familiarity, clinging on to the parts of the house that you can recognise even through the darkness and the grain, only for the rug to be pulled out from under you when those familiar elements are shown again in a different arrangement, or upside down or altered in some other way. The end result is a vivid evocation of feeling your way through the dark corners of your house as a child in the middle of the night, the familiar spaces becoming suddenly unrecognisable and potentially home to unspeakable horrors. The graininess of the film further exploits this feeling, where the textures begin to play tricks on your eyes searching for some sort of pattern. You may start seeing faces and figures in the darkness which aren’t there and, of course, anything you’re imagining is worse than whatever the film could conjure up. Eventually, when there is something lurking in the darkness, it feels almost otherworldly, like seeing the face of some incomprehensible demonic entity.

Skinamarink is the most terrifying cinematic experience in years. It’s unlike anything else you will ever see. It is not for everyone. But it is for me.

Skinamarink can be seen for a limited time at Lido Cinemas in Hawthorn and The Astor Theatre in St Kilda now.