A Blank Buffet: The Documentaries of Les Blank

Gap-Toothed Women (1987, United States, 31 mins)

Directed by: Les Blank

Written by: Les Blank

Produced by: Les Blank, Chris Simon

Cinematography: Les Blank

Edited by: Maureen Gosling

Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers (1980, United States, 50 mins)

Directed by: Les Blank

Produced by: Les Blank

Cinematography: Les Blank

Edited by: Maureen Gosling

Always For Pleasure (1978, United States, 58 mins)

Directed by: Les Blank

Produced by: Les Blank

Cinematography: Les Blank, Maureen Gosling

Edited by: Maureen Gosling

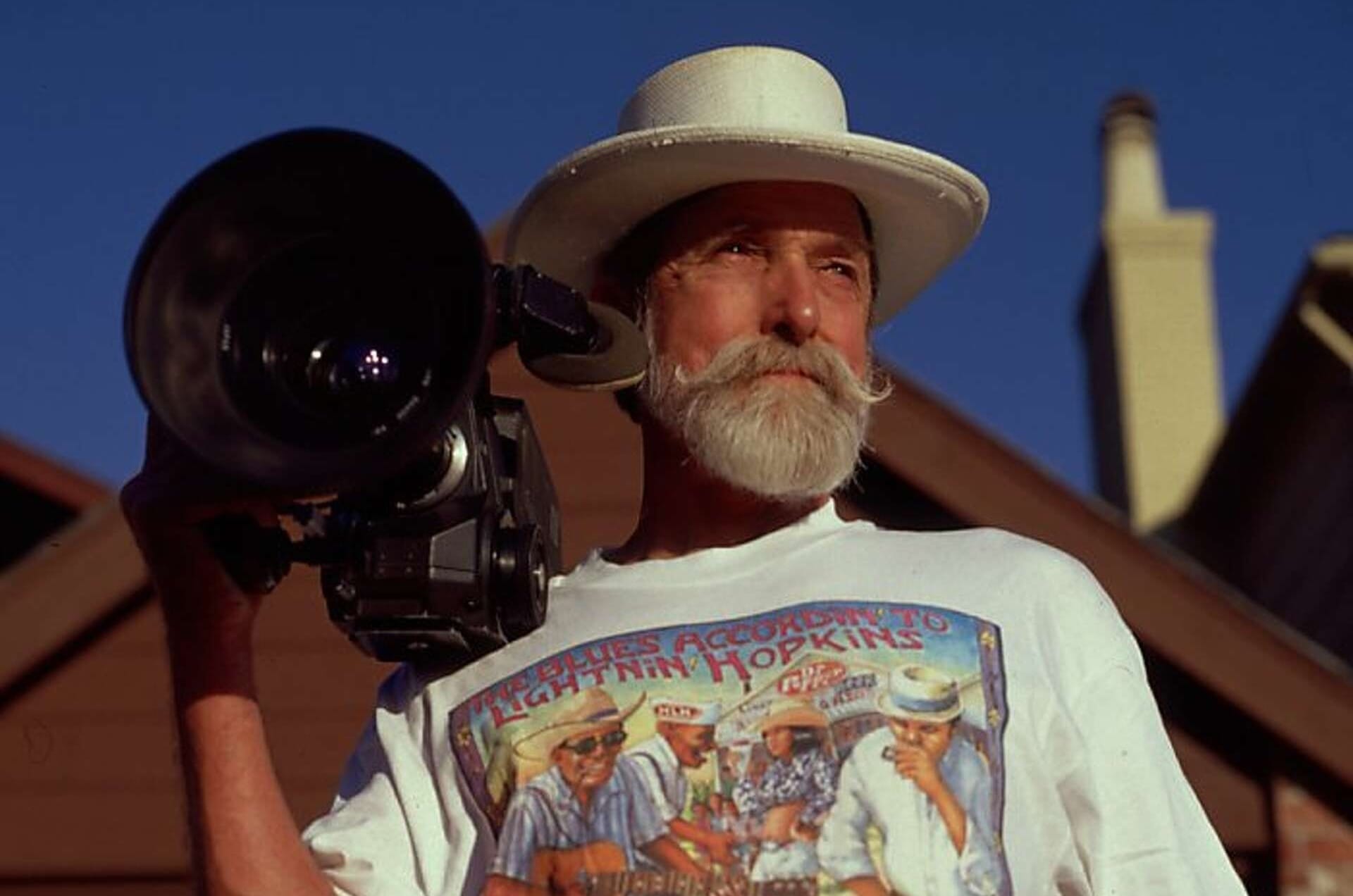

“Life is short. Art is long. Experience difficult.” – Inscription on Les Blank’s tombstone

While Les Blank’s documentaries are frequently aligned with cinéma vérité, Andrew Horton insists that “he goes cinéma vérité one better: his on-the-scene ‘motion’ picture work is cinéma vitalité”[1]. Horton’s distinction here is subtle – Blank certainly uses cinéma vérité techniques in his filmmaking – but strikes at the brilliance in how Blank puts together a documentary. Brad Prager elaborates that “the term vitalité does not denote representing a culture ‘as it is’, but rather aspiring to imitate its highest pleasures and most pronounced rhythms as vibrantly as is possible within the confines of the cinematic frame”[2].

Blank’s films are deeply personal, borne not just out of a desire to strike at the truth of his subjects, but out of an earnest admiration and – perhaps more importantly – enjoyment of his subjects. “His films clearly pull him, and us, into the lives he is following” Horton writes[3], highlighting the key function of a Les Blank documentary – the sharing of experiences. As Nick Pinkerton puts it, “Blank's camera-eye is as much that of participant as observer, though his digressive drifts are never purposeless, nor is the quality of invitation in his films an accident”[4].

Blank documentaries are community-focused films. Regardless of whether Blank’s subject is something as specific as a single Blues musician, or something as broad as garlic, Blank goes to great pains to explore, present, and share the cultures and communities which celebrate and produce whatever his documentary is about.

Blank’s favoured subjects – chiefly food, music and dance – point us towards holistic explorations of the communities surrounding them. These are the things which connect these people to each other and, through these films, us to them. Blank’s documentary Yum, Yum, Yum! A Taste of Cajun and Creole Cooking (1990) goes deep on how to make dishes like Gumbo or Étouffée, but also dedicates significant time to the Cajun and Creole cultures which produce them. Their traditions and music are given almost as much significance as the food itself.

It’s difficult to find even a second in any Blank film where there isn’t music playing. “Poetry and music are closely related,” Blank once said, “and I like to think the images I use are similar to the words: the two sort of blend together. Transitions are based on your senses rather than your thoughts”^[5]. Where Blank and long-time collaborator Maureen Gosling may edit together several different shots in service of presenting disparate aspects of a single community, the music playing over any given scene is the sensory thread weaving these images together. The music Blank uses is, however, very specific. It is either vernacular music specific to the marginalised community which Blank is presenting or a piece with a very literal connection to his subject – for example, the use of Ruthie Gordon’s ‘The Garlic Waltz’ in Garlic is as Good as Ten Mothers (1980). It’s this earnest love for music which brings Blank’s filmmaking out of the realm of ethnography and breathes life into it; the images captured on his 16mm Eclair camera begin to sing and dance on the screen. In Blank’s own words: “Well, for me, film without music is like a French cafe without wine, like a day without sunshine”[6].

Gap-Toothed Women (1987) is a “common-sensical, inspiriting paean to the mystery and variety of ordinary experience”[7], in the words of one New York Times writer. The film sees Blank interviewing a number of women with spaces between their front teeth, exploring their relationship to this unique beauty feature. Blank delves deep on cultural beauty standards, wholeheartedly rejecting the assumption that gap teeth are unattractive. Blank clearly has an enormous amount of love for gap-toothed women and yearns to share the beauty he sees in them with the rest of the world. To this end, the film is full of shots “composed in unusually stylized manners wherein his subjects’ distinctive smiles appear at the centre of the frame”[8], highlighting the charm of their unique grins.

Garlic is as Good as Ten Mothers (1980) is a zesty song of praise to the much-maligned stinking rose, exploring how different people and cultures interact with garlic in both their cooking and broader societies. Filmed at the Gilroy Garlic Festival in Gilroy, California, the film took 5 years for Blank to complete, leading Andrew Horton to write that “in time, personal funding, sweat, and psychic involvement, it is his Apocalypse Now”[9].

Unlike Coppola’s epic, Blank’s film is, like all of his films, unabashedly about celebration and positivity. Blank’s highlighting of the particular relationship different cultures have to garlic is intended as a unifying statement; the story of how this one plant connects people from all over the world. Blank even went so far as to suggest that several heads of garlic should be roasted in the cinema while showing the film – a concept he called Smellaround – so that the entire theater would be filled with the scent of garlic.

Nick Pinkerton writes that “this isn't just ethnographic William Castle showmanship, but gets at an important aspect of Blank's films: there's something about them that seems to chafe at being bound to the dimensions of the screen, to demand to be out and about in the wide world”[10].

Always For Pleasure (1978) sees Blank turn his cinematic eye towards the singular music and street celebrations of New Orleans. Blank was closely associated with the state of Louisiana throughout his career, making several films about marginalised ethnic enclaves in the state. In contrast to his films about Cajun and Creole culture, Always For Pleasure is focused entirely on the city of New Orleans and the specific culture of street celebration which gives the city its vibrancy.

Blank shoots jazz funerals, second-line parades, Mardi Gras and more, documenting the cultures which these celebrations arise from. “What is so entertaining about Blank’s work is that it succeeds both as film art and as research documentation” Robert Gordon once wrote[11].

Blank’s film draws together food, music and dance cultures alongside contextual histories of slavery and racial exploitation which provide a complete portrait of what makes these street celebrations so special and historically significant. But, above all else, the film is joyous and light, a celebration of celebrations made the way only Les Blank knew how.

References

[1] Andrew Horton, ‘A Well Spent Life: Les Blank’s Celebrations on Film’, Film Quarterly 35, no. 3 (1 April 1982): 27, https://doi.org/10.2307/1211924.

[2]Brad Prager, ‘On Blank’s Screen: Les Blank’s Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe and the Gravity of the Director’s Subject’, Studies in Documentary Film 4, no. 2 (1 January 2010): 126, https://doi.org/10.1386/sdf.4.2.119-1.

[3]Andrew Horton, ‘Les Blank’s Cinéma Vitalité’, The Criterion Collection, accessed 27 February 2025, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3381-les-blank-s-cinema-vitalite.

[4]Nick Pinkerton, ‘WHEN WE DANCE.’, Sight & Sound 25, no. 2 (1 February 2015): 94–95.

[5]Horton, ‘Les Blank’s Cinéma Vitalité’.

[6]Gloria J. Gibson-Hudson and Les Blank, ‘Excerpt from an Interview with Les Blank’, Black Camera 6, no. 1 (1 April 1991): 7–7.

[7]Vincent Canby, ‘Film: “Gap-Toothed Women,” “Miss . . . or Myth?”’, The New York Times, 16 September 1987, Gale Academic OneFile, https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c62f45ef-cbf8-3560-9b41-b65a602079b9.

[8]SPrager, ‘On Blank’s Screen: Les Blank’s Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe and the Gravity of the Director’s Subject’, 129.

[9]Horton, ‘A Well Spent Life: Les Blank’s Celebrations on Film’, 32.

[10]Pinkerton, ‘WHEN WE DANCE.’

[11]Robert Gordon, ‘Always for Pleasure Les Blank’, The Journal of American Folklore 92, no. 364 (1 April 1979): 261–261, https://doi.org/10.2307/539409.